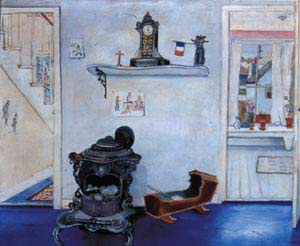

Sometimes in the winter I fancy that the woodstove secretly powers me, that I am set to the rhythm of its ticking metal parts, that the little pinwheels of flame spinning up through its coals are propelling the engines of my thoughts. It’s what happens when I spend too much time by the fire — too much time tending it and too much time lounging in front of it on chilly evenings like this one. I would like to be out admiring the stars that sprinkled the eastern sky so heavily after sunset, or listening for the screech owl that trilled outside our window until 2 a.m. the other night, but the talkative, yellow-eyed stove has me in its thrall. Faint clicks and clangs — the sounds of metal getting hotter — come from the aluminum pipe that hooks it to the flue, and as the fire burns brighter the pipe beats faster, a fevered metronome that is ignored by the clock ticking on the mantelpiece and the cat washing the back of his ear with languorous movements of his front paw. But I cannot ignore it. It tells me I should shut the damper, which I do. Then come the waves of heat that crinkle the air above the stove. A cobweb on the ceiling twitches in the updraft. Soon the armchair, the ottoman, the right flank of the sofa and the front half of the coffee table will be enveloped in a luxurious pocket of warmth, and the cat will finally fall under the spell of his cast-iron deity on the hearth. Already the contours of his neat black silhouette have begun to slacken. Another log thrown on the fire, another five minutes for the flames to build and he will be lying prostrate on the floor at its feet. He is as much of an idolater as I am — I who eat, sleep and dream by the fire.

In the morning it will be different. In January or February the first thing I look for when I wake up is the red light glowing in the woodstove’s scuffed mica window — a sign that the floorboards will be warm enough to stand on with bare feet and that the coffee won’t go cold in its cup between the slicing of the bread and the buttering of the toast. It is hard to describe what a primal comfort that light is in the bluish dark of a winter dawn, when the wind has been blowing all night long, pasting the windows with snow. But in March it begins to seem less meaningful. It is losing its battle with a more powerful light. Every day for the last few weeks the sun has been getting stronger, firing its own red coals — the cardinals — and in the morning we find ourselves more distracted by the white rays flickering in the curtains than by the stove-light burning on the hearth. Our attention shifts outdoors — to the gentle conflagrations in the garden, where a ring of purple shoots is pushing up through the stalks of last year’s phlox, and to the sea. At Race Point on Friday, the late afternoon sun showered the water with fat gold sparks. Only on these chilly March nights does the stove-light become vital again, but we know its time is running out. Every day from now on, a little less attention will be paid to the replenishing of the kindling basket, a little less time spent twisting last month’s news into papery hors d’oeuvres for the fire. Then one morning a few weeks from now, we will wake up and hardly even notice that the scuffed mica window has gone dark. The spell will be broken. Spring will be here!

(Saturday, March 19)